Today I’m happy to be hosting Jeffrey Stayton, who’s written a novel set in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War called This Side of the River. Over to Jeffrey!

Nostalgia

One of the most difficult aspects of writing historical fiction, especially about the Civil War, is the fact that too often the language of honor and glory from the era works its way into these narratives at the expense of portraying the actual horrors of war. Although This Side of the River is a work of fiction (and speculative history at that), I ruthlessly researched in university, state and county archives for years before even formulating the first drafts. What I found most important to me was not so much the dates, the names, nor even battle descriptions so much as how each writer expressed himself or herself in their respective memoirs, letters-to-home and war-journals and diaries. I soon created a document where all of these interesting words, mispronunciations and unusual turns of phrase were placed for safekeeping. It was important for me to know that if you though a road was passable back then, you more likely than not said it was “practicable.” My favorites were fun expressions, such as the oath, “May rosined lightning strike me dead” if I tell a lie. Those details found their way into the final draft that is nowThis Side of the River.

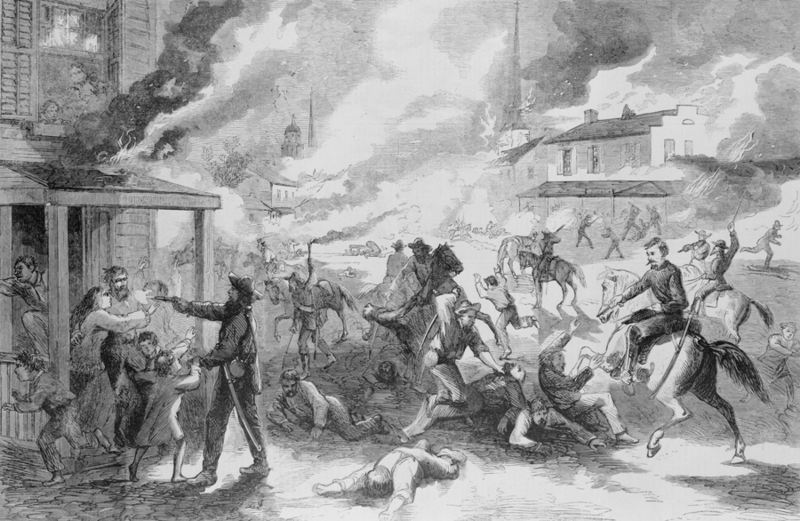

What struck me next came much later in drafting this novel. Not long after the Afghan and Iraq Wars were waged, we began seeing men and women return from battle suffering from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) syndrome. They returned in large numbers because our medical science is advanced enough to allow more dying soldiers to live, yet our civilization has not yet advanced to where we recognize that war is not simply “all Hell” as Gen. William T. Sherman famously put it: war is waste. It is a waste of “blood and treasure” and more often wars beget wars, setting the stage for the next conflict with similar bloody outcomes. So I grew interested in how Civil War soldiers suffering from PTSD dealt (or couldn’t) deal with the trauma. I learned that the term for this syndrome was often called, “nostalgia” or “soldier’s heart,” though many still regarded such things as an expression of simple cowardice. At the same time, my novel, which had been an 1861-1865 narrative, was turning into a post-Civil War story set in the summer of 1865. I felt like the post-apocalyptic South was a better environment for expressing “nostalgia” not only in soldiers, like Cat Harvey, but also the civilians who survived Sherman’s March to the Sea, like the warrior-widows who advance my story.

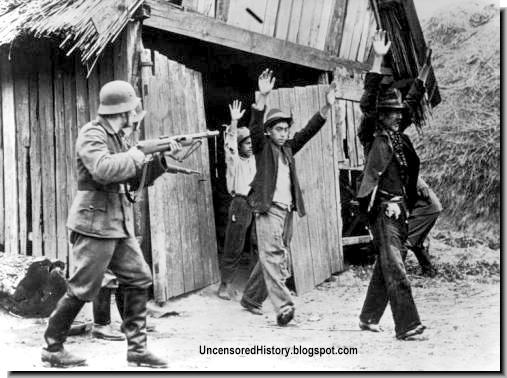

All of this I obviously found fascinating, though I had to look for other source material than simply Civil War documents. I began reading war-stories from many 20th and 21st Century conflicts to access the horrors of warfare without the veiled language of honor and glory getting in the way, whether this was Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam War story-cycle The Things They Carried or Ishmael Beah’s account of being a child soldier in the Congo in A Long Way Gone. What is clear is that the adults who should have protected their children from such bloodshed nonetheless insist on enlisting these boys, many literally children, into their wars. And then we expect them to somehow metabolize those horrors for the rest of their lives and grow to become good citizens. It is simply sick.

Finally, This Side of the River went through thousands of pages (I’m not exaggerating here) before I found page one of what would become my novel. By then I knew I was telling the story of Cat Harvey, a nineteen-year-old who had committed war crimes with a Confederate black-ops unit known as Shannon’s Scouts. What little we know of them speaks to the dark heart of the matter—pointblank shootings, reenslavement of recently freed slaves—and those were the things documented. I imagined even worse crimes primarily for two reasons. Whenever Gen. Joe Wheeler rode with Col. Shannon and his scouts, he rode under the alias, “Priv. Johnson.” Why did he do this? What were they doing that required this name change? Moreover, I was struck by the fact that Col. Shannon himself declined a Texas newspaperman’s encouragement to write his memoir about the Scouts heroic deeds. Shannon declined, citing that some Confederate sympathizing Northerners would be punished for their involvement. This somehow rang false to me as I read it. In a time when every soldier, especially colonels and generals, wrote of his heroic deeds in the Civil War, why not Alexander Shannon? This is where historical record ends and speculative historical fiction begins I suppose. So I found that I not only needed to explore this heart of darkness in Civil War lore, I needed to tell it in a style that dramatized it: the mosaic narrative. Once I began letting the various Georgia war-widows tell their stories, a shattered, cubistic portrait of Cat Harvey emerged that I felt worked.

I’ll leave it for the readers to decide on that one.

Synopsis:

This Side of the River is a novel set in in Georgia in the summer of 1865, after Confederacy has collapsed. A contingent of war widows who have survived Sherman’s March have armed themselves and rallied around a teenage Texas Ranger named Cat Harvey in order to ride north to Ohio and burn Gen. Sherman’s home to ashes. It is a story about trauma, revenge and redemption. What happens when they light out for Ohio is a terrible, doomed odyssey that forces these young women to ask the darker questions of the human condition.

Bio:

Jeffrey Stayton grew up throughout Texas and lived in Mississippi before landing in Tennessee where he’s lived with his wife in Memphis for the past four years. The southern author releases his first literary noir novel in February 2015, the 150th anniversary year of the Civil War’s end. This Side of the River was inspired by his question of what would have happened if the war-widows of Georgia took up arms in the aftermath of the Civil War?

He earned his Ph.D. in English from the University of Mississippi and specializes in 20th Century American literature.

He writes poetry, has written book reviews for the Missouri Review and has published stories in StorySouth, Lascaux and Burningword Literary Journal. His original story “Pepper” won the Bondurant Award for Fiction, and his story “Chisanbop” appeared in the Best of Carve Magazine.

He is a scholar and teacher of Modernist, Southern and African-American literature, often teaching women’s literature courses as well. His passion for Latin American literature brought Stayton and his wife on a hike across northern Spain on the Camino de Santiago where he brushed up on his Spanish.

When not writing and teaching, he’s in his studio working on oil paintings.

Having at one point performed standup comedy, Stayton embarks on a unique book tour in Winter 2015 gearing up to be as entertaining as the pages within his literary fiction.