The Crystal Ball, John William Waterhouse, 1902, Private Collection.

I’ve been fascinated by Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester for ages now and have been longing to post about her, however as I don’t feel massively confident about her period, I asked the author Susan Higginbotham to write a piece about the so called ‘witch duchess’…

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Eleanor Cobham.

For a few years in the fifteenth century, Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester—an adulteress and the daughter of a mere knight—was within a heartbeat of becoming queen of England. Instead, she ended her life a prisoner, bereft of her wealth and forcibly divorced from the man who had brought her to the pinnacle of English society.

Eleanor was a daughter of Sir Reginald Cobham of Sterborough and his first wife, Eleanor Culpepper. In the early 1420’s, she entered the household of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainault, who had taken refuge in England in 1421 after repudiating her husband John, Duke of Brabant.

Henry V, the English king, died in August 1422, leaving his infant son, Henry VI, as his successor. Henry V’s younger brother, John, Duke of Bedford, governed in France, while his youngest brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was named protector of England during the young king’s minority.

Jacqueline’s cause of recovering Hainault from her estranged husband and of recovering Holland and Zeeland from her uncle, John of Bavaria, attracted a powerful supporter, Duke Humphrey. Her person may have attracted him as well, for by February 1423, Duke Humphrey and Jacqueline had married. In October 1424, the pair landed at Calais. Eleanor, as a member of Jacqueline’s household, accompanied them.

What ensued was not Duke Humphrey’s most shining moment. Though Humphrey managed to recover much of Hainault, he soon met a determined opponent in Philip, Duke of Burgundy, who himself advanced into Hainault in March 1425. Humphrey had never been a popular figure in Hainault, and with the locals turning their support toward Burgundy, he decided to give up his adventure abroad. Probably he was also worried about what moves might be made against him in England during his absence. In April 1425, then, Humphrey departed for England, leaving his wife Jacqueline to fend for herself. He would never see her again.

Also returning to England was Eleanor, said by the chronicler Jean de Waurin to not wish to stay any longer in foreign parts. Described by Aeneas Sylvius as “a woman distinguished in her form,” and by Waurin as “beautiful and marvelously pleasant,” Eleanor soon became Humphrey’s mistress. Later, it would be claimed that Eleanor employed the witch Margery Journemayne to prepare drinks and medicines to induce the duke to “love her and to wed her.”

Jacqueline, meanwhile, doggedly continued to fight for her rights while awaiting the results of a papal inquiry into the validity of her marriages. Humphrey had not abandoned her entirely. In 1427, the king’s council allotted 9,000 marks for him to return to Hainault with an army, but the Duke of Bedford, fearing the consequences of such an action, intervened and brought Humphrey’s rather half-hearted preparations to a standstill by entering into negotiations with the Duke of Burgundy. More bad news for Jacqueline followed in January 1428, when the Pope ruled that her marriage to Duke Humphrey was invalid.

Eleanor’s relationship with Humphrey had not gone unnoticed. Sometime between Christmas 1427 and Easter (20 April ) of 1428, a group of women from London, “of good reckoning, well appareled,” came to Parliament, where, the chronicler Stow later reported, they delivered letters to Humphrey, the archbishops, and other lords “containing matter of rebuke and sharpe reprehension of the Duke of Gloucester, because he would not deliver his wife Jacqueline out of her grievous imprisonment, being then helde prisoner by the Duke of Burgundy, suffering her to remaine so unkindly, and for his public keeping by him another adulteresse, contrary to the law of God and the honourable estate of matrimony.” Their complaints had no effect on Humphrey. He could have remarried Jacqueline despite the papal ruling, as her first husband was dead. Instead, he married Eleanor Cobham, to general opprobrium.

It is not clear how long Eleanor and Humphrey had been lovers before their marriage. Humphrey had two illegitimate children, Arteys de Cursey (otherwise known as Artus or Arthur) and Antigone, who later married Henry Grey, Earl of Tankerville. It has been speculated by many, including Humphrey’s biographer K.H. Vickers, that Eleanor was the mother of these two children, but this seems unlikely. If Eleanor was indeed their mother, it is hard to imagine why Humphrey, who had no legitimate children, did not attempt to legitimatize Arteys and Antigone after his marriage to Eleanor, as John of Gaunt had legitimized his children by Katherine Swynford after he made her his duchess. Furthermore, Eleanor was later to confess to employing witchcraft in order to bear a child by Humphrey—an odd statement if she was already the mother of two of his children. It is also notable that after the deaths of her father and of Henry Grey, Antigone left England and married Jean d’Amancier, esquire of the horse to King Charles VII of France, which suggests that she had connections in France, presumably through her mother.

On 25 June 1431, Eleanor was admitted into the fraternity of the monastery of St. Albans, of which her husband was already a member. The following year, she joined an even more select group: the ladies’ fraternity of the Order of the Garter. Her Garter robes were awarded on 26 March 1432. Later, in 1440, the king gave her a New Year’s gift of a “Garter of Gold, barred through with bars of Gold, and this reason made with Letters of Gold thereupon, hony soit qui mal y pense, and garnished with a flower of Diamonds on the Buckle, and two great Pearls and a Ruby on the Pendant and two great Pearls with twenty-six Pearls on the said Garter.”

Eleanor’s status underwent a drastic change in September 1435, when John, Humphrey’s older brother, died. As the fourteen-year-old Henry VI was childless, Humphrey now stood next in line to the throne. The king gave Eleanor fine New Year’s presents to match her status. In 1437, her gift from Henry VI was “a nouche maad in mane of a man garnized with a fayre gret bal” and with a “gret diamand pointed with thre hangers garnized with rub . . . bought of Remonde goldesmyth.” Even Eleanor’s father benefitted: the high-ranking Charles, Duke of Orleans, who had been taken prisoner by the English at Agincourt, was transferred into his custody.

Eleanor was in her glory — and knew it. Ralph Griffiths reported, “One chronicler noted how she flaunted her pride and her position by riding through the streets of London, glitteringly dressed and suitably escorted by men of noble birth.” She was even accused of extortionate practices against the almsmen of the Hospital of St. John at Pontefract.

For all of his faults, Duke Humphrey was a cultured and intelligent man, with a love of books, and it is likely that Eleanor shared his interests. She is said by Vickers to have owned Sloane MS 248, described by him as a “semi-medical, semi-astrological work translated from the original Arabic.” And it was Eleanor’s interest in astrology that would prove to be her downfall.

On either 28 June or 29 June 1441, Eleanor, dining in her usual high style at the King’s Head in Cheapside, heard of the arrests of three of her associates, Master Roger Bolingbroke, an Oxford priest who also served as Eleanor’s clerk, Master Thomas Southwell, a canon and a rector, and John Home, a canon who also served as Eleanor’s chaplain and secretary. The three men were accused of conspiring to bring about the king’s death.

Bolingbroke had once composed a tract for his “esteemed and most reverend lady [probably Eleanor], in the mother tongue, concerning the principles of the art of geomancy.” Now he apparently implicated her, stating that she had commissioned him to predict her future— not a trivial manner for a woman whose husband was next in line to the throne. Soon he and Southwell would be indicted for sorcery, felony, and treason. Bolingbroke was accused of having contacted demons and other malign spirits, and he and Southwell were both accused of having used astrology, with Eleanor’s encouragement, to predict the king’s death in the twentieth year of his reign. A nervous Henry VI promptly commissioned an alternative horoscope, which neatly refuted the horoscope drawn by Bolingbroke and Southwell. (If the new astrologer, whose identity is not known, had learned that Henry would live another thirty years, but would die as a prisoner in the Tower of London, probably through foul play, he wisely omitted this prognostication.)

Eleanor, meanwhile, had fled into sanctuary. On 24 and 25 July, she was examined at St. Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster, on twenty-eight charges. J.G. Bellamy points out that as she appeared before ecclesiastical instead of secular authorities, she was likely being investigated for heresy and witchcraft instead of treason; the lack of precedents for trying a peeress for felony and treason probably saved her from such charges. Eleanor admitted five of the charges, the precise details of which have not survived.

It was probably at this point that Eleanor acknowledged using the services of Margery Jourdemayne, known as “the witch of Eye.” Margery, from a yeoman family, had already been imprisoned for witchcraft; in 1432, she had been released on good behavior. Jessica Freeman suggests that since that time, she had continued to discreetly offer clients love potions and charms, such as those allegedly used by Eleanor to entice Humphrey into marriage.

Meanwhile, Eleanor had been ordered to await future hearings at Leeds Castle. Fearful of leaving sanctuary, she feigned sickness and attempted to escape by water, but was found out. On 11 August, she was escorted to Leeds by members of the king’s household. Eleanor remained at Leeds for the next two months. On 19 October, she returned to Westminster, where she was again examined by an ecclesiastical tribunal at St. Stephen’s. At a second hearing on 23 October, she was confronted with Bolingbroke and his instruments, and admitted to employing them only to conceive a child by Humphrey. Southwell and Margery also appeared at the hearing, where they accused Eleanor of being the “causer and doer of all these deeds.” She was found guilty of sorcery and witchcraft.

While imprisoned in the Tower, Southwell escaped his probable fate by dying “of sorrow” on 26 October; Freeman suggests that he might have taken poison in order to escape the death of a traitor. The next day, Margery, who had been found guilty of heresy and witchcraft, was burned at Smithfield. Bolingbroke, found guilty in a trial before the King’s Bench, was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn on 18 November. Home, who had been indicted only for having knowledge of the activities of the others, was pardoned and continued in his position as canon of Hereford. He died in 1473.

What was Humphrey doing while all of this was unfolding? Over the past couple of years, his differences with the king’s other advisers over foreign policy and the rise of other men in the king’s favor, especially William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, meant that he had become increasingly marginalized. There was little he could do to assist his wife. Perhaps he was also shocked at her activities, in which he had not been implicated. As Vickers points out, though, he may not have been entirely passive, as an edict was issued forbidding interference in the proceedings against Eleanor, and she was heavily guarded on her trip to Leeds.

Whatever protection the duke could have offered his wife ended on 6 November 1441, when a commission of bishops ordered that Humphrey and Eleanor be divorced. The couple would never meet again.

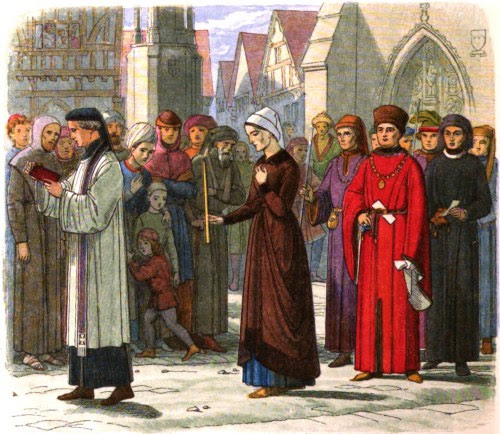

Three days later, Eleanor was ordered to do public penance for her sins. On 13 November, bareheaded and dressed in black, carrying a wax taper, she was taken by water from Westminster to the Temple landing stage. Led by two knights, she walked from Temple Bar to St. Paul’s Cathedral, where she offered her taper at the high altar. Two days later, she walked from the Swan pier in Thames Street to Christ Church, where she again offered a taper. On 17 November, with the familiar taper in hand, she made a third journey, from Queenhithe to St. Michaels in Cornhill. The citizens, plenty of whom were on hand to witness her humiliation, had been ordered neither to show her respect nor to molest her.

Her public penance ended Eleanor’s public life. In January 1442, she was sent to Cheshire; the king, evidently bearing Eleanor’s previous feigned illness in mind, ordered that the journey not be delayed due to any sickness on her part. She was allowed 100 marks per year and had a household of twelve people—a considerable comedown for the proud duchess. In October 1443, she was taken to Kenilworth; during her stay there, King Henry sent her a canopy with curtains for her bed. In July 1446, Eleanor was transferred to the Isle of Man. In March 1449 she moved for the last time, to Beaumaris in Wales. On 7 July 1452, she died at Beaumaris, where she was buried at the expense of Sir William Beauchamp, the constable of the castle there. Few chroniclers noted her death, and it was not until 1976 that her date and place of death was established.

Humphrey did not long survive his wife’s disgrace. In February 1447, he set off for a meeting of Parliament at Bury St. Edmunds. One chronicler wrote that he hoped to obtain a pardon for his imprisoned wife. Instead, he was arrested, for reasons too complicated to go into here. He died several days later on 23 February, probably of a stroke, although murder was rumored. A number of his retainers, including his illegitimate son, were arrested and convicted of treason, but were pardoned immediately before they were to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Among the charges against them was that they had been attempting to free Eleanor Cobham.

The Duke of Gloucester was buried at St. Albans, and, thanks largely to the unpopularity of Henry VI’s ministers, soon acquired a posthumous reputation as “Good Duke Humphrey.” As for Eleanor’s legacy, it would be to add a footnote to legal history. In 1442, Parliament cleared up the question of how peeresses charged with treason or felony were to be tried by enacting a statute declaring that just like peers, they would be judged by the judges and peers of the realm.

(For lovers of historical fiction, Eleanor Cobham is one of the subjects of Jean Plaidy’sEpitaph for Three Women. She is also featured in Claude du Grivel’s Shadow King, which I haven’t read. Humphrey and his family feature in Juliet Dymoke’s Lord of Greenwich and in Brenda Honeyman’s Good Duke Humphrey. Jacqueline is the heroine of Hilda Lewis’s I, Jacqueline.)

The penance of Eleanor Cobham.

Sources:

J. G. Bellamy, The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge: 1970.

Hilary M. Carey, Courting Disaster. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Jessica Freeman, “Sorcery at Court and Manor: Margery Jourdemayne, the Witch of Eye next Westminster.” Journal of Medieval History, 2004.

James L. Gillespie, “Ladies of the Fraternity of Saint George and of the Society of the Garter.” Albion, 1985.

Ralph A. Griffiths, King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century. London: Hambledon Press, 1991.

Harris Nicolas, Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England, 15 Henry VI to 21 Henry VI, vol. V. 1835.

Ruth Putnam, A Mediaeval Princess. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

K. H. Vickers, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. London: Constable and Company, 1907.

Thanks Susan! Susan Higginbotham is author of wonderful historical fiction, most recentlyQueen of Last Hopes: The Story of Margaret of Anjou and Her Highness, the Traitor

about the women behind the ill fated crowning of Lady Jane Grey.