Invasion

When Isabella, Edward’s estranged queen, and his foremost enemy, Roger de Mortimer landed on British soil near to the manor of Walton in Suffolk on 24th September 1326, Edward was taken by surprise. Not so much by the invasion itself, as he had been preparing for such an event for the past couple of months – but that the force they brought with them was so small. It consisted of about 1500 soldiers (exiled Contrariants and Hainault mercenaries) – hardly enough to constitute a great threat. However, if Edward thought his wife and Mortimer’s rebellion a pathetic gesture, he was soon forced to think again.

When Isabella, Edward’s estranged queen, and his foremost enemy, Roger de Mortimer landed on British soil near to the manor of Walton in Suffolk on 24th September 1326, Edward was taken by surprise. Not so much by the invasion itself, as he had been preparing for such an event for the past couple of months – but that the force they brought with them was so small. It consisted of about 1500 soldiers (exiled Contrariants and Hainault mercenaries) – hardly enough to constitute a great threat. However, if Edward thought his wife and Mortimer’s rebellion a pathetic gesture, he was soon forced to think again.

As the force swept towards London, it seemed to collect supporters along the way. Or, more correctly, officers in the parts of Essex an Hertfordshire ordered by Edward to raise an army against her, refused to do so and joined her campaign instead. This was only the beginning of a very large landslide of support to the cause of the rebels. Gathering strength, Isabella and Mortimer’s army now headed for the capital with the intention of forcing Edward to surrender.

Realising that he was now in danger, Edward decided it would be prudent to leave London. On October 1st he transferred Mortimer’s sons to the Tower for safe-keeping and the custody of the castle was given into the hands of Hugh’s wife, Eleanor and John Weston. The next day, Edward and Hugh left the capital along with the king’s supporters and household, the Great Seal and a large amount (about £29000) of money.

Flight

On October 3rd, the King’s party had reached Acton. These days it may seem as if he hadn’t travelled very far in that time, but in the 14th century, due to the state of the roads, Acton was actually about half a day’s journey from the capital. It was also a normal stopping off place for travellers on the London to Oxford road. Here, Edward issued commands for his ships (one of which was called ‘La Depensere’) to arrest suspicious persons sailing on the Thames and to carry out searches for people carrying ‘suspicious letters’. In hindsight, this looks like closing the stable door after the horse has bolted – but maybe Edward was expecting further hostile forces to follow the main invasion party.

From Acton they travelled to Wallingford, just south of Oxford and thence to Gloucester, where they arrived on 10th October. At this point Roger and Isabella had reached Dunstable in Bedfordshire and were heading towards Oxford in pursuit. In Gloucester Edward sent out requests to John Wake, John Inge, John de Toucestre and others to assemble men at arms in their various counties and to bring them to the king. He also sent out a proclamation pardoning any previously imprisoned malcontents if they would side with him against the rebels.

After three days in Gloucester, Edward and his group travelled through the Forest of Dean, stopping at Westbury on Severn along the way before finally reaching Tintern Abbey on the 14th October. Here Edward started to appoint men to protect the March, the Forest of Dean and Wales. Donald of Mar, one of Edward’s most faithful retainers was sent into the March along with the soon-to-be turncoat Hugh de Turpington to ‘punish the disobedient’. However, it was while the king was staying at Tintern that the opposition delivered some punishing blows. Many of the men Edward had hoped were loyal to him (and were bringing forces to defend him and the country) had already defected to Isabella’s banner. Now the Queen issued a proclamation that she was not invading the country but that she had come to save it from the evil of the Despensers. With such a righteous-sounding cause that presaged no harm to the King himself, many more joined her ranks. The Londoner’s too, rose up against the king and riots broke out. The entire city, apart from the Tower (which managed to hold out until November 17th) fell to rebel hands and any Despenser properties were looted, as were those of their agents in the city. Another loyal friend, Walter de Stapledon, was captured and viciously murdered by a mob.

Wales

From Tintern, the King’s company fled to Chepstow Castle, where Hugh Despenser the elder was appointed to the custody of Bristol Castle. Although not mentioned in any record that I have seen, it can be supposed that he took a boat from Chepstow to Bristol to take up his duty in that city. Meanwhile, Edward now heard that Henry of Leicester – Thomas of Lancaster’s brother – had also now defected to Isabella. His loyalty had been in doubt anyway, but his desertion was still an enormous problem as Henry, like his brother – had large numbers of men and they were now committed to the enemy cause instead of his own. In a rather ineffectual damage limitation exercise, Edward sent Hugh’s son Hugh (the even younger) along with Donald of Mar, Edmund Hacluyt and Bogo de Knovyll (also of dubious allegiance) to seize the earl’s castles of Grosmond, Skenfrith and White Castle in the marches.

On October 21st, Edward, Hugh, Baldock and several others set sail from Chepstow. Their proposed destination is unknown. It has been suggested that it was Lundy island (which Hugh owned) as supplies had been sent on ahead to it. However it is also possible that their eventual destination was Ireland – or anywhere where the beleaguered king might find some support (I think I shall look at this issue in another post as I don’t really have the room here). But whatever their intentions, the weather was against them and, despite the prayers of Hugh’s confessor for a fair wind, they spent five days getting nowhere in the Bristol channel until they were finally forced to put into Cardiff on 27th October.

Their stay in Cardiff was short as they were at Caerphilly Castle – Hugh’s great Welsh stronghold – by the 29th. Here, Edward made a last desperate attempt to raise support amongst his Welsh subjects – but to no avail. It has been suggested that perhaps they remembered Hugh’s execution of their rebel leader Llewellyn Bren in 1318 and were thus unsympathetic to his and the king’s plight. This may be the case, but it may also be that they knew a lost cause when they saw one and didn’t wish to be seen to be on the wrong side. It was around this time that he and Hugh must have been informed that Bristol castle had fallen and Hugh the elder had been executed by hanging. His eldest son, prince Edward had been declared as the guardian of the realm in the king’s absence and Henry of Leicester had been authorised to take a force into Wales and arrest him.

Edward and Hugh must have now known that the last stages of the crisis were being played out. Edward issued an order to purvey supplies for the castle of ‘corn, bread, ale, flesh, fish or other victuals’ for ‘the maintenance of the king and his men there’. Although similar directives were given to supply Chepstow and Bristol, this order has a more urgent feel to it. It also gives the impression that the king was planning to stay there as a sort of last stand. And if that was what was planned then Caerphilly – an impregnable, immense fortress was the best place for him to stage a last stand.

Desperation

However, despite the proximity of Isabella and Mortimer, now at Gloucester, and the dangers posed by Leicester’s forces, it seems that Hugh and Edward decided on one last desperate ploy. By now, most of their households had deserted them – probably for fear of what would happen if (or rather when) Isabella and Mortimer prevailed. It seems, though, that Edward had not yet given up hope for some kind of settlement. Leaving Hugh’s son and the very capable and loyal John Felton behind to guard Caerphilly, Edward, Hugh, and a small band of their retainers rode out for Neath abbey – via Margam abbey – arriving on the 6th November. On the 10th, Edward issued safe-conducts to the abbot of Neath, Rhys ap Gryffydd, Edward de Boun, Oliver de Burdegala and John de Harsyk to go and negotiate with Isabella and prince Edward. However, the negotiations came to naught – as far as the real power-holders (Isabella and Mortimer) were concerned any surrender was to be unconditional.

Edward and Hugh stayed in Neath for nearly a fortnight – a surprisingly long time when Henry of Leicester was breathing down their necks and when Isabella and Mortimer certainly knew where they were (from the negotiating party, if nothing else). Most probably they considered themselves safe while they thought talks were taking place. Once their ambassadors returned with the bad news, however, it was clear that they were in the most serious clear and present danger and that it was probably a good idea to make a quick move.

Capture

What happened next can only be gleaned from the chronicle writers, as the last official record was written at Neath on the 10th (in the Patent Rolls). Most versions say that Edward and Hugh’s exact whereabouts after leaving the abbey were betrayed to Leicester, but the betrayer varies from a Cistercian monk to Rhys ap Howel. The location of their capture also varies from being near Neath to a small place known as Pant-y-Brad (Hollow of Treason) close to Tonyrefail. I will also discuss this in a future post but suffice to say for now that I personally think the latter location is the most likely. It is close to Hugh’s castle at Llantrisant and also not far from Caerphilly Castle – where I believe they were headed.

The story goes that, on November 16th, during a terrible storm, Edward, Hugh, Baldock and a handful of retainers including Simon of Reading, Thomas Wyther, John Beck, John Blunt, John Smale and Richard Holden were ambushed by Leicester’s men. Although surprised, the men managed to take flight and were pursued for a short distance until they were overtaken and captured. Although the party was later split up (some released and others taken to various places of imprisonment), it seems that they were first held at Hugh’s own Llantrisant Castle – maybe overnight while Henry’s men rested both themselves and their horses. The fate of the king was still unsure but for one man in particular – Hugh Despenser – it must have been completely certain that he was now a dead man walking.

Main Sources:

Calendar of Close Rolls

Calendar of Patent Rolls

The Greatest Traitor – Ian Mortimer

The Tyranny and fall of Edward II 1321-1326 – Natalie Fryde

Pictures

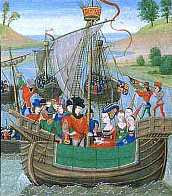

Top – Isabella arrives at Orwell (from the Froissart Chronicles)

Bottom – Caerphilly Castle