CRACKS IN THE DUTCH DEPORTATION AND DETENTION REGIME

HELEN HINTJES

AHMED PURI

June 13, 2013 — Comment

Written by Helen Hintjens & Ahmed Puri

A series of hunger strikes, following allegations of abuse, force and the use of forged documents, are showing up the fault lines in the Dutch detention system.

For the first time in more than a decade, hundreds of people in Dutch immigration detention centres have gone on hunger strikes in protest at their hopeless situation. In late May, two young Guinean men moved from Rotterdam detention centre to the prison hospital in Scheveningen in The Hague, were reported to be suffering from kidney failure as a result of dry fasting. One of them, Issa Koulibaly, a 22-year-old who has written long and eloquent letters to his lawyer and supporters, explaining exactly what has been happening to him in detention,[1] states in his letters that if forced to return to Guinea, he would rather die.

At the same time that Issa and others like him are being victimised for daring to take action to defend their rights, hunger strikes are spreading in Dutch detention centres, with dozens if not hundreds of detainees taking part. In early June 2013, the Ambassador of Guinea in Brussels denied that his Embassy had signed a number of laissez-passer documents somehow ‘obtained’ for Guineans whom the Dutch authorities wanted to deport.[2] It is not the first time that such systematic malpractice has been alleged.

Issa Koulibaly

Issa also provided evidence that already in 2012, false travel documents were being created so that the Dutch authorities could send failed asylum seekers to Guinea Conakry. When Issa went to the Guinean Embassy in Brussels in October 2012, they refused to provide him with travel papers, on the grounds that his return was evidently not voluntary. And the Embassy still insists that it has not signed any of the laissez-passers currently being used by the DT&V (Dienst Terugkeer en Vertrek or the Repatriation and Departure Service of the Dutch Immigration and Nationality department). In the efforts to deport unwanted detainees like Issa, it seems that even forgery may be acceptable.

Cracks are appearing in the Dutch asylum detention and deportation regime – cracks that grow wider as one scandal after another on individual cases of neglect, abuse, forgery and violence pile up. The forgery issue was already debated in parliament in 2012, when a Guinean delegation of four people was reported to have run up expenses of over €115,000.[3] More recently, just as disturbing as the resort to fraudulent papers, are the growing number of reports from inside detention centres of the massively one-sided use of violence against individuals on hunger strike. Issa’s case, for example, suggests that the violence being acted out on detained individuals, often in isolation cells, is of a level to cause serious injury. If this is confirmed (and it seems to be confirmed by doctors and lawyers alike) then this use of force amounts to torture. As one ‘GreenLeft’ (Groen-links) Dutch MP, Arno Bonte, puts it, the regime in the Rotterdam detention centre now has elements that resemble what goes on at Guantánamo Bay.[4] By a strange coincidence, a large number of Guantánamo Bay detainees have also been on hunger strike for several months, and around one third are now being force fed.[5] Earlier this year, the Dutch High Court decided it was legally acceptable to force feed hunger strikers in Dutch detention centres too.[6]

A wave of protest

Aleksandr Dolmatov

This wave of hunger strikes and protests is connected with the Dutch government’s current review of proposals to criminalise undocumented people, and a related review of asylum policies. The suicide in April of Aleksandr Dolmatov, a member of the Russian opposition and a rocket scientist who sought asylum after being arrested by the Russian authorities, was another trigger. After Dolmatov’s death, investigations showed his case was improperly handled by staff, and that a combination of human and computer error meant he was wrongly issued with a rejection, and then placed in detention. He should, by rights, have been granted asylum, and had this been the case, he almost certainly would still be alive.[7] Dolmatov’s suicide put Secretary of State for Justice and Security, Fred Teeven, under intense pressure in parliament following a highly critical Ministry of Justice report on the case. Teeven responded by using his discretionary powers to grant asylum to one of the detainees who had been on a life-threatening ‘dry fast’ in Schiphol detention centre.[8] Perhaps unwittingly, the Secretary of State thus played his part in setting off a new wave of hunger strikes nationally. The Dolmatov case also helped ensure that hunger strikers would receive some positive attention in the Dutch media and parliament.

The present protests started in late April, more or less spontaneously in all detention centres across the country, beginning with Schiphol. Some of those leading the hunger strikers in detention have lived in the Netherlands for many years, sometimes decades.[9] They are well-connected people, who have contacts among support organisations, in the media and with lawyers who will represent them. Together with the more recently arrived, like Issa Koulibaly and Cheick Bah, the two Guineans in Scheveningen prison hospital in early June, who both complained of violence, beatings and mistreatment, many have written eloquent letters about their situation. Issa sent letters to the new King Willem Alexander, to parliamentarians and to the press.[10] Organisations like PRIME (Participating Refugees in Multicultural Europe), the Fabel van de Illegaal (the Myth of Illegality), Deportatieverzet(Deportation Resistance Group) and Anti-Fascist Action, an anarchist group, have all been active protesting in solidarity with detainees, whether in the centre of cities like The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam or in the form of noisy protests outside the detention centres themselves.[11]

The roots of the present crisis lie in the impossible position in which refugees from countries like Somalia and Iraq find themselves. Expelled from asylum reception centres, they are thrown onto the streets, even in winter, not allowed to work or study, and in some cities cannot even stay in homeless shelters. They either cannot or will not return to their home countries, which are at war. In 2011, rejected Somalis were the first to organise themselves outside Ter Appel reception centre, and to create the organisation, Vluchtelingen op Straat (Refugees on the Street), based in Utrecht. Through this they demonstrated in The Hague and elsewhere, and later a related tent camp was set up in Amsterdam. This became the Vluchtkerk or ‘Refugee Church’ action, from December 2012 to May 2013. This was the first time that refused refugees started to organise themselves nationally across the country rather than within specific localities. The Somalis were the first. Iraqis too started to organise themselves, and from September to December 2012 created a tent camp in The Hague. They too ended up in an empty church, this time in The Hague. (Read an IRR News story: ‘The Hague: Refugees evicted from protest camp‘) Each time destitute asylum seekers try to hold peaceful protests, the government responds by either ignoring them, or by detaining protestors, including Iraqis and Somalis, those whom they cannot hope to deport. Whilst some municipal authorities offer destitute protestors temporary shelter, the tone is set by the Ministry responsible. Both former Minister for Refugees, Leers and now Secretary of State Fred Teeven, insist that hunger strikes are ‘blackmail’ which ‘will not work’. Yet hunger strikes, camps and other peaceful actions are surely legitimate forms of protest, under extreme circumstances, in the absence of any other form of dialogue. ‘I wonder who is really blackmailing who?’, asks PRIME. ‘It seems the government is saying it will not listen until hunger strikers stop their action. Then they get people to stop, by promising them many things, but they lie.’

A disturbing feature of the authorities’ non-response to the hunger strikers’ demands has been an apparent escalation in the use of physical force inside Dutch detention centres against individuals. As Ministry of Justice guards are gradually replaced with G4S and other private security guards, the situation seems to be deteriorating. Perhaps fearing they will lose control of detention centres, special security police are now being used against detainees like Issa Koulibaly and Cheick Bah, as confirmed by Bah’s doctor, Elcke Bonsen.[12] The shocking treatment of a Malian woman, who arrived in the Netherlands with her passport and visa in order, was detained and whose papers were subsequently ‘lost’ by the authorites whilst she was in detention, is the subject of a horrifyingly effective video.[13] The National Ombudsman of the Netherlands is very outspoken in describing the detention regime as ‘soul destroying’. Even worse, as well as breaking the spirit of those detained, the regime is rife with allegations of medical neglect and gratuitous violence by special ‘emergency’ police, the IBT (Intern Bijstand Team or Internal Preparedness Team). Detainees in isolation cells are particularly vulnerable to physical punishment for refusing to end their hunger strikes, as punishment for other forms of self harm or to enforce their compliance with deportation enforcement. A recent report by the equivalent of HM Prison Inspector, the Adviescommissie voor Vreemdelingenzaken (ACVZ) was presented to parliament at the end of May 2013, and detailed many abuses of detainees, including medical neglect, poor record keeping, physical violence and punishment in isolation cells for the slightest infringement of rules. The Secretary of State Fred Teeven simply responded that he was not surprised by these findings. The report concluded that instead of being used as a last resort, detention was being used routinely in ways that were inappropriate and unjustified. For national groups who cannot be deported, like Somalis and Iraqis, detention is even harder to justify.

The case of Issa Koulibaly

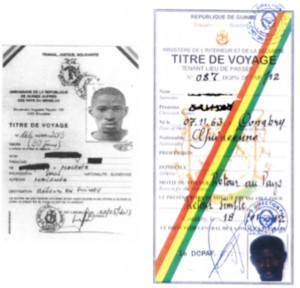

Issa came to the Netherlands in 2009 as a young man, not yet 18. He had been involved in student demonstrations in Guinea, had been imprisoned, tortured and then fled the country. The Dutch immigration authorities accused him of not being Guinean, and yet as Issa points out, now they want to deport him to Guinea in any case. Issa was in detention, first in Rotterdam, and then at Scheveningen hospital. He documented his case in a series of long and articulate letters in French to his lawyer and other supporters. His detailed letters from detention in May to June 2013 are translated into Dutch.[14] From the prison hospital in Scheveningen, his letter explains that he has been kicked and assaulted by the IBT, water-hosed when he tried to set himself on fire after slashing himself with a broken plate. He also reports how they told him he would have to leave Holland, and gave him a laissez-passer which appears to be a forgery. It is shown below on the left, along with another example of a forged document (note that the photo is placed over the stamp, rather than being stamped as is normally the case).

Two examples of travel documents that appear to be forgeries. Issa Koulibaly’s is on the left

Issa’s lawyer is confident that Issa’s letters are reliable, and based in fact. His stories are similar to recent comments from the Scheveningen prison doctor who suggests that the other Guinean, Cheick Bah had experienced violent abuse at the hands of the IBT and that his body was covered in bruises.

Both were kicked and hit, and were also systematically maltreated over a longer period, being placed in isolation, being woken up repeatedly at night, and having to sleep with the light on all night. Issa started his hunger strike in mid-May and has fallen unconscious several times. He wants to have his case reviewed and says he prefers to die in the Netherlands than be sent back to Guinea, where he fears he will be arrested and tortured again. Prison conditions in Guinea are notoriously brutal and corrupt, and the Dutch government knows this. Nonetheless, in 2012 four people were sent to Guinea, and these included people from other countries besides Guinea. According to a report in Nieuwsuur about the 2012 cases, one Guinean woman was refused entry when she arrived in Guinea because her papers were not genuine. In the 2012 cases, it was concluded that the travel papers had not been provided by the Guinean Embassy in Brussels, as they should have been, but by a special team coming from Guinea, all expenses paid.

The Dutch authorities want to deport Issa Koulibaly, who, together with Cheick Bah, was recently moved to Scheveningen prison hospital from Rotterdam detention centre, suffering from kidney failure. Bah’s doctor has gone on national news in the Netherlands to state that in her view he was tortured through sleep deprivation and physical violence.[15]

In a letter he sends to his lawyer, Issa explains that false travel documents were being provided in mid-May by a ‘Task Force’ from Guinea pretending to be from the Embassy. In 2012 Gambians, Malians, Senegalese and Sierre Leoneans had all been sent to Guinea with false papers. ‘Which country would have its Embassy inside a prison? I refuse to meet these people’, he adds, and concludes by stating that he feels death is the only way out for him. ‘Sometimes life gives you no choice.’ In his 19-page handwritten letter, Issa described how after he was told he would be deported with the (forged) papers provided by a special visiting Guinean delegation, he started to cut himself with a broken plate. Bleeding, he then set fire to his blankets and wrapped himself in them. He states he did this quite deliberately to avoid deportation to Guinea. ‘If I could return, why would I prefer to die? I was not a suicidal person, but the situation I found myself in forced me to take this course of action.’ He then alleges he was sprayed with cold water for several minutes. After the water hosing, the IBT arrived and forced him flat onto the ground. They wore helmets. ‘They violently attacked me without mercy. Some of them kicked me with their shoes, others beat me with their batons. I cried with pain as they tried to put my hands behind my back. They put cuffs on my hands and feet. These cuffs cut my skin, and caused me even more pain, because of my wounds. They carried me like a piece of luggage as I cried out in pain and prayed to God.’

One doctor alleges serious mistreatment of those kept in isolation cells, including sleep deprivation, keeping the lights on in cells, 24-hour observation. Even the lawyers of those mistreated may not be informed when they are moved from one detention centre to another. Psychologically and physically, the aim seems to be to break people down, destroy their spirit of resistance and their will to protect their own interests. It was at the point that Issa finally refused to accept the papers he had been told were being prepared by the Guinean delegation. As Issa explains in his letter: ‘It was not at all like the real document. The stamp was only that of the second consul. There was no name written next to the signature. The validity was for 90 days … I do not believe this is a real laissez passer. It is forged.’

On 4 June, Issa was due to be deported, and this was delayed on 3 June by the court in the first instance for a week. Earlier in October 2012, the Guinean Embassy in Brussels had already refused to provide papers for Issa’s deportation, on the grounds that his removal was not voluntary. However, another Guinean delegation came to Holland on 13-17 May 2013, no doubt once again with all expenses paid. Issa, in detention in Rotterdam, was told by his DT&V officer that he will be deported. When he heard that he would be travelling on false papers, Issa decided to end his life. As he explaied in his letter: ‘Sometimes death is better than life. I will be free (if I am dead). I will leave with some memories of a short moment of happiness in Holland, and a long period of misery. However, I do not have any bitterness against anyone. It is God who has wished things to be so. Since I will be a corpse with no-one to claim me, no papers and no family, I would ask that those who take charge of my body to give me a burial in accordance with Muslim customs. I would ask that they not use my organs or remove them for use by another person, for the love of God. I would like to rest in peace.’

Widening cracks in the system?

Bushra Radibi, a councillor in Utrecht, confirms that officials came from Guinea in May 2013 for a few days, and provided papers that were not genuine. The impression was that the Dutch authorities were not too keen to know who signed the papers, so long as they could get rid of the Guineans they wanted deported. Mamadou Diallo, organiser of the Guinean community, expressed surprise that the Embassy was not involved, in the proper way. Sharon Gesthuizen of the Socialist Party asked several questions in parliament, but there was no clarification of why Guinean delegations were brought to the Netherlands no less than five times in the past few years. Huge expenses were alleged, with generous per diems and expense accounts totaling €117,000. According to reports in the news, they stayed in the Hilton and ran up shopping bills. Questions were asked in parliament about what on MP described as this ‘deportation tourism’. Sharon Gesthuizen described the trade in migrants as a ‘cattle market’.[16]

IBT is only supposed to be used for emergencies or calamities

The IBT seems to be being used more since detention centres in the Netherlands started relying on private G4S security staff instead of Ministry staff. According to Issa and other detainees, the private security guards have a very short training period, and know almost nothing about the rights of detainees. Mistreatment may be viewed by hard pressed and inexperienced staff as a means of controlling detainees, through fear.

Governments cannot get away with brutality of this kind indefinitely. Recent high-profile cases in the UK, for example, show that NGOs like the Helen Bamber Foundation and Medical Justice can defend victims of torture who have been wrongly detained. The Dutch authorities still seem not to fear being sued. In April 2013, the UK Home Office was ordered to compensate a group of torture survivors wrongly held in UK immigration detention centres. In future, could similar cases be taken up by lawyers and asylum support organisations in the Netherlands as well?

RELATED LINKS

Read an IRR News story: ‘The Hague: Refugees evicted from protest camp‘

Read an IRR News story: ‘The fear that stalks asylum seekers from the Russian Federation‘

Read other IRR News stories on the Netherlands